A picture, it used to be said, was worth a thousand words. But with today's digital technology, it can be any thousand words you would like. And not one of them may be true. If you've ever pondered the covers of magazines like Spy (Hillary Clinton posed as a dominatrix comes immediately to mind), or any recent photograph which makes Liz Taylor look gorgeous, you're at least subliminally aware of what computers can do, and how easily they can make the camera lie.

Doctoring photographs is nothing new, of course. Historical figures have been moved in and out of photos almost at will by people with good darkrooms and questionable scruples. When Mao Tse-Tung was rumored to be deathly ill (or even dead), the Chinese Communists produced a photo of Mao bobbing in the ocean with a host of comrades. Of course, the shadows on his face didn't match those of his swim buddies, and the head itself seemed somewhat disembodied, but it may have convinced some people that the head of state was still able to hang ten with the best of them.

There were more subtle fakes, of course, but such work required a highly skilled photographer with a well-equipped darkroom. But today, almost anyone with a desktop computer and the right software can produce fakes that are far more convincing than even the finest darkroom production. And the skilled technician can produce a forgery that is almost impossible to detect.

The most common software used to manipulate photographs (and not always dishonestly; my next article, in fact, will show how technology can bring back bits of the truth) is Adobe Photoshop. Originally designed as a means to enhance images that had been converted from photographic originals to digitized copies, Photoshop has grown up to become a virtual darkroom...and beyond.

When a photo is digitized, it is converted into dots, known as pixels. Each pixel carries a piece of information about the original image: for a black and white photo, it records white, black, and 255 shades of gray; for color, it can record any one of 16,000,000 hues. Because the image is broken up into individual pixels, the degree of photo editing extends to the smallest image detail--with patience, one could alter each pixel, one at a time, to produce seamless blends of information. (In fact, some photographers now eschew the darkroom in favor of the computer screen, because it allows them a far greater degree of control over the final image.)

Photoshop can perform all of the standard darkroom tricks. It can alter tone, color, contrast and brightness, can selectively blur or sharpen portions of an image, can darken or lighten specific areas (called "burning" and "dodging" in the traditional darkroom), as well as produce "negatives," or even create "solarized" images (a combination of positive and negative images). But, through the application of what are called "filters," Photoshop can also produce effects that would prove difficult or impossible in the darkroom: one can, for example, turn a photo into a mosaic, a sample of needlework, a bas-relief, a pen sketch, or a painting!

More importantly, one can "import" other images--either photographs or drawings--into the original photograph to create a picture of something that never existed in reality. (There's a good reason why Adobe calls Photoshop "a camera for the mind"!) And once the pieces have been put together, all the ragged edges--those "unnatural" shadows in Mao's face, for example--can be smoothed out, pixel by pixel, if need be.

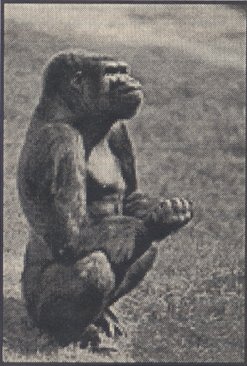

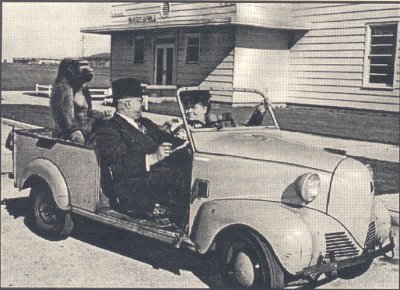

To produce the photos accompanying this article, I began with two images: Henry J. Kaiser and his wife Bess sitting in a rather silly looking truck (courtesy of the Bancroft Library), and a gorilla (obtained from a photo CD of "stock images"). The photo of the Kaisers was scanned ("digitized") into Photoshop, and cropped to the desired proportions. A few "errors" in the original were ironed out (most notably, a flaw in the top center of the building, caused by damage to the original picture), and then the area behind Henry J. was "selected--that is, an electronic "line" was drawn around the area, making it into a sort of "window." Any image placed within that window will replace the pixels of the original image with its own.

Next, the gorilla was "selected," which means that all of the background was removed, in this case by painting an electronic "mask" around the gorilla. Anything painted in red remained "unselected," leaving only the beast itself surrounded by a "marquee" of moving dashes (called "ants" by Photoshop users). This selection was then "copied" onto the "clipboard" (an electronic storage bin) and then "pasted into" the selected area of the original photo. Since the proportions of the two photos were not the same, the gorilla had to be "resized" (proportionally!) until it was in scale with its human companions. Once that was accomplished, the gorilla was moved into position in the "window" that had been created for him (since the side of the truck was not selected, the gorilla vanishes when it comes into contact with the truck). While still "selected," the gorilla was "feathered"--that is, the pixels at the edges of the selection were faded out a bit so that the added image would blend more smoothly with the original photo. All that remained was a bit of touchup (mostly in the area where the gorilla comes into "actual" contact with Henry's suit).

Voila! With a half hour's work, I produced a photo that could make a monkey out of almost anyone. Especially Mr. Kaiser, were he alive to see it.

![]()

Telephone: 925-229-1042

Fax: 925-229-1772

e-Mail: info@cocohistory.com