Nearly 160 years ago, gold was found in California, a discovery which transformed the rural Mexican hinterlands into a booming state. On Jan. 24, 1848, a diarist in Coloma wrote "this day some kind of mettle was found in the tail race that looks like gold."

Gold fever gripped the population, emptying Alta California's cities and changing California forever. In the span of a year, the pastoral days of Hispanic culture were ended as the energetic and chauvinistic Americans came to mine and stayed to settle. San Ramon Valley pioneers were part of it all.

Some, like Mary and John Jones, Joel and Minerva Harlan, Leo and Jane Norris, William and Mary Lynch and Jose Maria Amador were already in California when gold was found. Others, including Andrew and Dan Inman, Albert Stone, R.O. Baldwin, William Meese and Felix Coats, came to California for the gold.

Our best stories about the early gold rush involve the Harlan family because of their links to Peter and Elizabeth (Jane) Wimmer, who were in Coloma that cold Jan. 24th. The Wimmers came to California because Joel Harlan's father, talked them into it. George Harlan had always possessed a touch of wanderlust, and when he read Lansford W. Hastings' book The Emigrants' Guide to Oregon and California, he decided to leave Michigan and strike out for the West Coast. His nephew, Jacob Harlan, wrote that George "declared that as soon as the harvest was over and his grain sold, he would sell his farm and leave for California."

A real apostle for the move, George brought his family and extended family along. According to his daughter, Mary Harlan Smith, he also "hunted up his (ex) brother-in-law Peter Wimmer who had moved to Missouri and persuaded him to join our party with his family." When George's sister died, Peter was widowed and he had remarried Elizabeth Baiz. Two first cousins, Jacob and Joel Harlan, were teen-agers on that trip and called the Wimmers "Aunt Jane" and "Uncle Peter."

The large Harlan-Young party (the other family contingent was headed by Samuel C. Young) arrived in California in 1846, barely escaping the early Sierra storms which sealed the fate of the Donners. The story of this trek is told in Jacob Harlan's book California, 1846-1888. Once in California, the Wimmers stayed at New Helvetia (later Sacramento) while the Harlans moved to the Bay Area.

Capt. John Sutter of New Helvetia had been looking for a better sawmill location for years. Finally, on Aug. 27, 1847, he signed a contract with James W. Marshall to erect and operate a sawmill at Coloma, about 45 miles from the South Fork of the American River. Marshall hired Wimmer as assistant, thirteen Mormons and some local Indians.

Marshall and sixteen year old John Wimmer left the fort on Aug. 28 to select the specific site for the mill and were soon joined by Wimmer's father Peter, Jane and the younger children. Jane Wimmer cooked for the crew, in addition to caring for her family.

Histories tell us James Marshall discovered some pieces of gold in the river as he inspected the progress of the mill work. Several tests were applied to the metal, including boiling it for hours in a solution of lye which Jane Wimmer was using to make soap. Jane had come from mining country and had panned for gold as a girl near Auraria in Georgia. Later she said that her son had brought her a nugget. "I said, 'this is gold, and I will throw it into my lye kettle, and if it is gold, it will be gold when it comes out.'"

A letter from Peter Wimmer to the Harlan boys told about his work on the sawmill and said their son had discovered the first gold. He wrote that the news was out, even though Sutter had tried to keep it quiet. According to the letter, Sutter, Marshall and Wimmer had taken the precaution of calling the local Indians together and leasing 12 square miles of land around the mill from them. No matter who found the first gold, news of easy riches at the surface of the American River spread quickly in California and beyond.

The gold rush and gold fever transformed California in two short years. The Harlans were there at the start. In April 1848, Joel Harlan and his cousin, Jacob Harlan, were running a livery business in San Francisco when they received a letter from their "Uncle Peter" Wimmer. He told them about the placer gold discovery and urged them to come to Coloma to mine immediately.

In his book California 1846-1888, Jacob wrote, "It upset all my business plans. I caught gold fever at once, and notified my wife and my partner Joel that it was time to give up livery stable keeping and go to the mines."

Sutter was trying to keep the gold discovery quiet. The news was printed first in The Californian on March 15, 1848. The Californian article read "Gold Mine Found. In the newly made raceway of the Saw Mill recently erected by Captain Sutter, on the American Fork, gold has been found in considerable quantities." This announcement did not elicit much attention at the time.

In May, however, a dramatic action by young Mormon Sam Brannan really set off the gold rush frenzy. He was an energetic entrepreneur with a store in New Helvetia (Sacramento). After being paid in gold by talkative local miners, he became convinced that the gold discoveries were legitimate and took steps to make money from the find. He stocked his store with all the merchandise he could get, went to San Francisco on May 12, 1848, and waved a bottle of gold dust in his hand, yelling "Gold! Gold from the American River!" Many historians mark the real beginnings of the California gold rush from that day.

That spring, Joel and Jake and their young wives left the livery business in San Francisco to set up a store in Coloma. According to Jacob, Joel put their horses to pasture at Squire Elam Brown's (in Lafayette) while he got a stock of goods "suitable for a store or trading post at the mines. Joel was a doubting Thomas and did not understand how we were going to start a store with five hundred dollars, which was our capital."

William Leidesdorff, a prominent landowner and civic leader in San Francisco, was a friend of the Harlans and agreed to advance them the money. Jacob said, "My purchases that day amounted to $4,500, for all of which Leidesdorff made himself responsible." Harlan bought the things miners would need: groceries, flour, beans, liquors, dry goods, shoes, tools, shovels, picks, tin pans, kettles and ammunition.

They took Capt. John Sutter's launch up the Sacramento River and hired two ox teams in Sacramento to get to Coloma. Jake turned down an opportunity to be a partner with Sam Brannan "being already in partnership with Joel."

Their Uncle Peter, still working on the sawmill, put them up in Coloma until they built a cabin. They found the miners would pay whatever "we demanded for our goods": flour cost $1 a pound, coffee $1.50. Jake made money selling colorful cloth with holes cut out as serapes to the Indians. Jake said, "They had much fine gold which they carried in vulture or goose quills." They loved the serapes and were not stingy. In one day, two bolts of fabric brought $1,200.

The Harlans weren't the only Californians to take off for the mines in 1848. Writers tell about the deserted streets and unfinished jobs in San Francisco, San Jose and Monterey. One young man wrote, "My own business of surveying, like all others, was knocked in the head last spring, and I was left to suck my thumbs for a livelihood or go with the multitude." Gold fever spread from California to the world as forty-niners arrived from Mexico, Europe and China.

Joel did some prospecting and returned one night with $1,600 worth of gold. He neglected to leave a tool to mark his ownership of the hole and found others in his place the next day. Life went on, gold rush or not, as cousin Jake Harlan's wife, Ann, had their first child on Sept. 9, 1848, at Coloma.

Jose Maria Amador went up in June and July of 1848, netting by his account $13,500 from mining and merchandise during one trip, and $10,000 more in another. He and his son took cattle and food to sell and brought 25 Indians with him from his Rancho San Ramon to work for the gold. Their camp came to be called Amador's and, later, Amador city and county were named for him.

The Harlan cousins sold their store in Coloma and returned to San Francisco, where prices had gone up astronomically. Chester Lyman wrote that a 50 square yard, unoccupied lot rose in value from $15 in 1846, to $400 the next year, to $10,000 in 1848. San Francisco's population went from an estimated 600 in early 1848 to over 20,000 in 1849.

Many others who later settled in the San Ramon Valley came from back east because of the gold rush. Felix Coats settled in Tassajara Valley in 1849. He wrote: Hearing so many tales of the rich mines in California, which caused such wild excitement over the whole country, my father and I, having caught the "Gold Fever," were anxious to try our luck.

R. O. Baldwin and William Meese came from Ohio and mined, eventually settling in Danville in 1852 and planting some of the earliest successful crops in the county that winter. Dan and Andrew Inman left Illinois in 1849 for the gold fields. Andrew began ranching in Green Valley in 1852 and Dan moved here for good in 1858, buying 400 acres which is today Danville's Old Town.

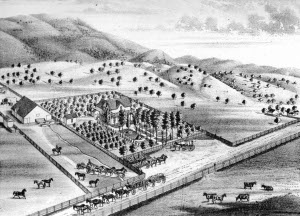

Joel and Minerva Harlan moved to the San Ramon Valley in 1852, using some of their earnings to purchase land from Amador and Norris. Minerva told her children there was so much gold around, she found it hard to believe that gold would be worth anything.

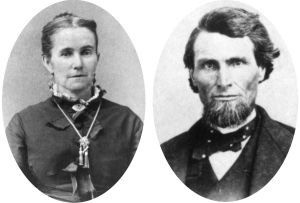

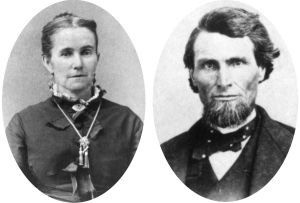

Their first house was listed as a landmark when Alameda County was carved from the original Contra County in 1853. In 1857-1858 they built a new Gothic Revival house, called "El Nido" which still sits at 19251 San Ramon Valley Blvd. in San Ramon. The Harlan's house and ranch land were well known and their nine children were among the builders of young California. Joel died in 1875 and Minerva in 1915.

The Wimmers fade from memory, except for the famous "Wimmer nugget." Elizabeth Wimmer claimed she had kept the original gold which had been tested in her soap pot. Until the day she died, she wore the gold in a soft buckskin bag around her neck. The gold piece is often displayed at the Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley.

J.P. Munro-Fraser in his 1882 History of Contra Costa County called the first Valley pioneers "birds of passage" who had been to the mines, felt the blessings of the "glorious climate of California" and returned to settle. They were part of a huge immigration which raised the population from 14,000 (not counting Indians) in the 1840s to 225,000 by 1852. California ultimately skipped the usual territorial stage and became a state in 1850.

Gold started California. Some historians suggest that the abrupt beginnings of the state, with a practically all-male cast of characters, was not the best way to begin a new community and a great state. Historian Kevin Starr, for one, called it a "rapid, monstrous, maturity."