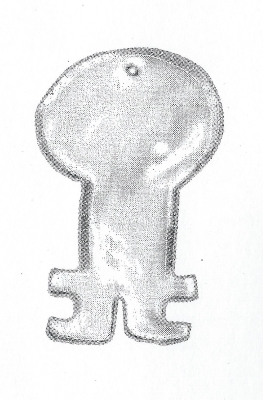

Courtesy, Museum of the San Ramon Valley

The First People

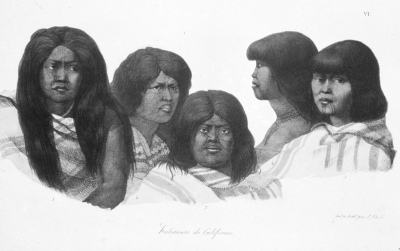

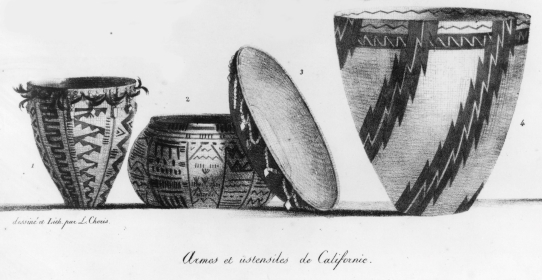

They called themselves "Real People." Today we call them Indians or Native Americans. While little information remains about the Valley Indians' specific culture, they would have had an intimate relationship with the land, a cycle of life which changed very gradually from generation to generation, and a tribal organization which owned the rights to hunt, fish, gather, and pray within clearly designated territories.

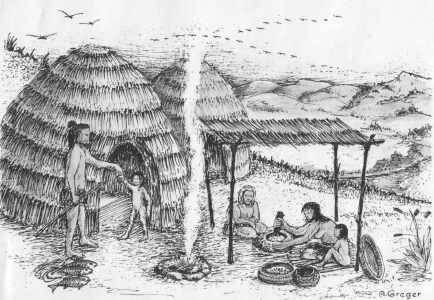

Living in village communities of 50 to 200 people, the rhythm of their lives was determined by one harvest or another. The Bay Area and the San Ramon Valley provided an infinite variety of foods, so the Indians collected acorns, nuts and seeds, fished, and hunted birds, deer and elk. At other times larger groups met for feasts and dances, probably at places like Danville by San Ramon Creek or at autumn festivals on Mount Diablo. Some people lived along the small streams and springs in the mountain's foothills either permanently or seasonally.

Sacred Mount Diablo

Mount Diablo was sacred to the valley Native Americans, as it was to other Indians who lived within sight of it. All Indian tribes had traditions and creation accounts which featured the mountain.

Each tribe had its name for the mountain. The Costanoan-speaking people south of Mount Diablo called it Tuyshtak. Early Spaniards named it Cerro Alto de los Bolbones (High Point of the Volvons) for the tribe which controlled the summit and eastern areas of the mountain. The name Mount Diablo (Devil's Thicket in Spanish) originated during a Spanish expedition around 1805. The superstitious Spanish soldiers called a willow thicket Monte Diablo when a group of Chupcan Indians from today's Concord escaped from them during the night. Later the name was transferred to the mountain.

The Spanish Arrive

In 1772 the first westerners traveled through the San Ramon Valley. In his diary for March 31, Father Juan Crespi said that they "came to three villages with some little grass houses. As soon as the heathen caught sight of us they ran away, shouting and panic-stricken." The next day he noted that the area had "level land, covered with grass and trees, with many and good creeks, and with numerous villages of very gentle and peaceful heathen...It is a very suitable place for a good mission."

Spanish missionaries first recorded the names by which San Ramon Valley Indians were known to their neighbors: Saclan, Tatcan and Seunen and Souyen. The Saclans and Tatcans were part of the Bay Miwork linguistic group. The Saclans lived in Lafayette and perhaps Walnut Creek, while the Tatcans probably lived in the Alamo-Danville area near the San Ramon Creek watershed. The Seunens and Souyens were Costanoan (or Ohlone) speakers and lived adjacent to creeks in San Ramon and Dublin.

In the fall of 1794 the Saclans were the first to go to a Spanish Mission in today's San Francisco. The Spanish weapons, their unusual gifts and music intrigued the Indians; some of them wanted to ally themselves with the powerful newcomers. But, only months after they moved to Mission Dolores, an epidemic swept the mission and, in the spring of 1795, the people fled the mission and returned home. For nearly ten years the Saclans and other neighboring tribes fought against the Spanish -- "gentle and peaceful" no more.

Mission San Jose

Founded in 1797, this Mission attracted Seunens beginning in 1801. It was only 13 miles from Mission Dolores. Seunens and Tatcans went to Mission Dolores as well. Had it not been for the hostility of these tribes, the Spanish would have placed Mission San Jose inland in today's Amador, Livermore, San Ramon or Diablo Valleys.

These valleys became part of Mission San Jose's grazing land. An Indian named Ramon lived in the San Ramon Valley tending Mission cattle and sheep during the winter months. Later he was an alcalde of the Mission Indians. His name was given to the Creek and Valley, with "San" added to conform to the Spanish usage of the day.

Ultimately contact with the Spanish destroyed the Indian way of life. The livestock ravaged their carefully nurtured meadows. Western diseases, and Spanish cultural and spiritual expectations altered Indian society forever.

The Rancho Era

In 1833, just as the Missions San Jose and San Francisco were being prepared for secularization, two Ranchos were granted by the Mexican government in the San Ramon Valley. Both were called Rancho San Ramon. The pastoral rancho era began, with lands carved from former Mission areas. The cattle and sheep brought to these Ranchos were former mission livestock. Cattle hides and tallow provided the economic basis for the Ranchos.

Jose Maria Amador's Rancho San Ramon eventually included over 20,000 acres, with his headquarters in today's Dublin. He employed Indian and Mexican workers and developed an industrial center which produced leather goods, harnesses, wagons and furniture. Mariano Castro and Bartolo Pacheco, owners of the northern Rancho, lived elsewhere because of the aggressive Indian tribes in the area.

Mission San Jose became a parish church with no more temporal control over the Indians in 1836. The Indians scattered to work on the Ranchos and at the Pueblo of San Jose. Some more recent recruits went back to their tribes in the Central Valley. On a rancheria in Pleasanton, called Alisal, Indians from different tribes preserved their customs and traditional religious practices for many years.

American California

When the Gold Rush began, it transformed California from a slow paced Mexican territory to an American state. Although the Indians controlled most of the inland area, thousands of miners invaded these traditional lands and decimated the tribes. California, which entered the Union as a free state in 1850, passed laws which allowed Indians to be enslaved by any white man. Children and young women were taken and sold as servants. Not until 1863, well into the Civil War period, was the so-called "Act for the Protection of the Indians" repealed.

There are 242,000 Indians in California in 1990, more than 80,000 of them California natives. Most live in urban areas, but many are still part of over 100 traditional communities.

The traditional Tatcan and Seunen villages of the San Ramon Valley are no more, although descendants survived and are working to preserve their language and culture. The artifacts unearthed next to creeks by bulldozers and the bedrock mortar holes on Mount Diablo remind us that a complex culture of great antiquity existed in this Valley just 250 years ago.