On the first Tuesday of each month, Directors of the Contra Costa County Historical Society gather at the History Center for our board meeting. As we scoot chairs around the main table for our 6:30 p.m. meeting our conversations frequently revolve around our unique and rather large archival holdings. It was no different at the December meeting, but this time our conversation turned a bit macabre: Someone brought out a mysterious, leather bound volume filled with individual photographs and descriptions of Contra Costa County criminals. Of course we had to put it away and begin our meeting, but the dark nature of the bound volume piqued my curiosity and I was determined to venture back to our archives as soon as possible and have a more thorough investigation.

My partner in crime was Andrea Blachman, fellow board member of the Contra Costa County Historical Society. We met at the History Center -- get this -- the day after Christmas at 10 a.m.. What we found were six separate archives all filled with people charged as Contra Costa County criminals. The oldest volume was a large, leather bound record entitled Descriptions and Photographs of Discharged Prisoners (From San Quentin, 1887-1920). Another volume, in less pristine shape, was Sheriff's Criminal Photobook, 1895 - 1906. In addition to these two large volumes, we also found four, smaller volumes of county criminal records that covered the early 1900's. For those of us familiar with Contra Costa County history these dates fit squarely into Sheriff Veale's tenure as County Sheriff, 1895 - 1934. Eager and rather curious to see what it was that we had found, Andrea and I sat down for a few hours, on that quiet day after Christmas, and perused the volumes.

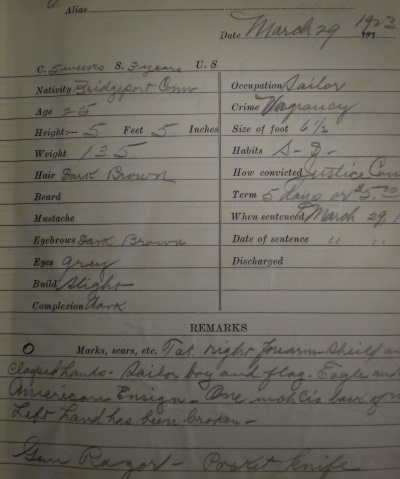

The faces in these black and white photographic records were unsettling, each person accused of a crime and sentenced stare back at you morosely. Next to the photo, and further down each individual page, Andrea and I saw exactly why each person was arrested. This was followed up by an eerie description of the person's features: "right hand crippled, fingers crumpled," or, Andrea found this one: "a really ugly bugger."

Most of the people arrested for crimes were white men. However, in the earlier volumes, the number of Chinese men arrested is noticeable and the witting photo display of each Chinese man's beautifully braided queue, wrapped loosely around his neck for the viewer not to miss, was clearly intentional. Andrea and I made note of one "Indian (from Montana)" whose occupation was a "tinsmith." The county criminal form duly noted that he committed burglary. But before we turned the page, we glanced back over the document and saw handwritten boldly across the top of the criminal form and underlined twice was: "Died in prison." In the 1923 volume, the word "Negro" was written in extra large letters next to a few men's names even though the attending photo stated the obvious and "race" was already a category on the form.

At the end of our perusal, it seemed to us that people had come from all over the world just to be arrested in Contra Costa County: Gustave from Russia, Otto from Norway and Barney from Wisconsin. Arrests for vagrancy were very common; punishment was "five days or five dollars." Drunk and disorderly punishment was "ten days or ten dollars." Andrea saw a lot of arrests for "indecent exposure." And frequently what people were arrested for corresponded with the historical tide, such as Prohibition. In the 1923 volume we lost count of how many men (and one woman named "Rosie") who were arrested for "possession of apparatus for manufacturing liquor," "possession of intoxicating liquor," "still operator" or, "manufacturing booze." Manufacturing booze, by the way, cost one man -- "whose left hand was crippled by an explosion" -- 300 days of his life. And let's not forget the teamster who was arrested for "operating an automobile under the influence of liquor."

Many of these records were humorous, in that Murphy's Law kind of way, but other records that we read caused Andrea and me to reflect upon whether lives in the county are any different today. For each person accused of a crime, like today, there is always a back story. We couldn't help but wonder what happened or why it happened that a man was arrested for "failure to send numerous children to school." He was sentenced to five days in jail. A farmer from Portugal was charged with the crime of "abandonment" and three days later another man was charged with "aiding the abandonment of minor children." A Greek man was charged with "wife beating." And lastly, a 27 year old man from Illinois of "stalwart build" who committed, in 1923, the crime of burglary died in jail. His "habit," listed on the county criminal form, was "narcotics."

It was hard to walk away from these criminal records: All of them gave testimony to lives in the balance. Each page seemed to call out to us, not so much for what they had to say, but rather for the whole back story that was missing. We wanted to figure out why the "housewife Eva" was sentenced to 90 days or $100 when no crime was listed on the county form. Why was "Pedro" (and not Bob) arrested for carrying a "concealed weapon?" And yet, we only had a few hours on that quiet day after Christmas to merely glance --and not sort out-- the lives of so many caught in the web of history.